Understanding Water Test Results

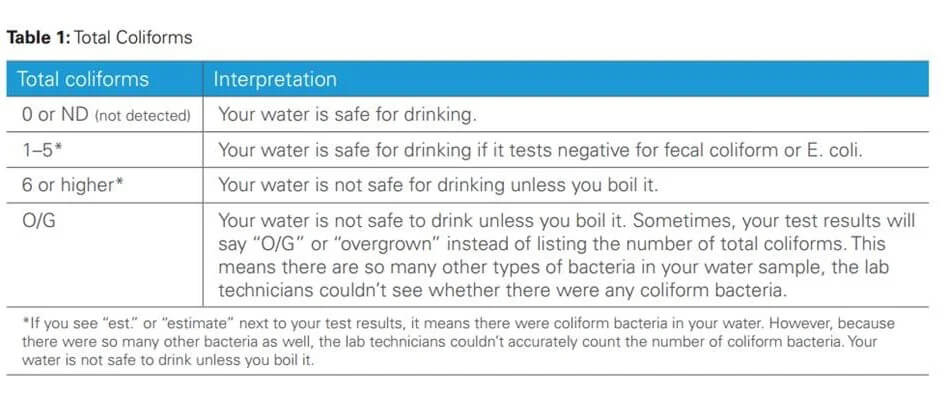

Different labs may present the results of a well water test a little differently, but one of the key results to look for is total coliform count.

Coliform bacteria are a group of bacteria that can come from many sources. You’ll find them living in soil and decaying vegetation, as well as in the digestive systems of humans and animals. So while most coliform bacteria are harmless, some are not.

If your test results show that there are coliform bacteria are present in your water, it is an indication that the quality of your well water is compromised and your well may be contaminated with surface water, manure or sewage.

How serious is this? It depends on how high the number is. Table 1 gives the Environmental Protection Agency’s Safe Drinking Water Standards. If your results are borderline, the lab may suggest retesting.

Fecal Coliforms or E. coli

As well as a total coliform count, your test results may include a fecal coliform count, or E. coli count. Fecal coliforms are types of coliform bacteria that live in the digestive systems of humans and animals. If your test results show any fecal coliforms, your water is likely contaminated with human sewage or animal manure. E. coli is an even more specific type of fecal coliform. If your test results show any E. coli in your water, it is not safe to drink unless you boil it.

What to do if my Water Isn’t Safe to Drink

While you’re addressing the source of the problem, boil your well water before you drink it or cook with it. To make sure it’s safe, bring it to a rolling boil for a full minute.

Shock Your Well

To remove bacteria from your well, one option is to “shock” it with a high dose of chlorine. The amount of chlorine you need depends on the depth of your well, the pH of the water and how much slime or biofilm is present. Keep in mind that chlorine is corrosive and should be handled with care. Leave the chlorine in the well for at least 12 hours and then purge the water. Highly chlorinated water is not safe to drink!

Better yet, call in a water treatment professional. An expert will know exactly how much chlorine is required and how to safely dispose of the chlorinated water once the shock treatment is complete.

It’s important to remember that shocking your well doesn’t offer a long-term solution for ongoing contamination issues. It’s a quick fix that needs to be paired with long-term inactivation.

Retest Your Water

After you’ve shocked your well, wait 24 hours and then retest the water. Next, wait a week or two and then test it again. Once you get two “bacteria-free” results, your water is safe to drink – for the time being.

If possible, address the source of contamination. Even once you’ve received an “all-clear,” don’t kick back and forget about drinking water safety.

If your well has been contaminated once, it may get contaminated again. By tracking down the source of the problem and fixing it, you’ll reduce the risk of your well becoming contaminated in the future.

There are several common sources of contamination:

- Heavy rain or flooding

- Leaking septic systems

- Agricultural runoff that contains manure, either from livestock operations or manure that has been spread on fields as fertilizer

Remember that many wells may draw water from the same aquifer. This means if your neighbors don’t maintain their wells properly, your water can become contaminated.

Check Your Well Water Regularly

Remember that the quality of your well water changes throughout the year. The EPA recommend testing your water at least once a year. Spring is a good time, when your well is most likely to become contaminated by spring melt, heavy rain or flooding.

You should also consider testing your water if:

- there is a change in land use nearby

- you notice a change in quality of water

- a member of your household experiences an unexplained gastrointestinal illness

Consider a Water Treatment System

Unfortunately, some problems can’t be fixed. If you can’t control the source of contamination, or you if you want additional peace of mind, consider installing a water treatment system that inactivates bacteria and other microorganisms.

There are a number of options. Point-of-use (POU) systems treat the water at a specific tap. So if you install a point of use system at your kitchen sink, for example, the water from your kitchen tap is treated. However, it means the water coming out of your bathroom tap is not. Point-of-entry (POE) systems typically cost somewhat more than POU systems; however, they treat all the water coming into the house, so you can turn on any tap knowing the water that comes out has been treated by a known treatment technology.

Featured Posts

La primera planta piloto de reutilización de agua potable en Europa utiliza Trojan UV AOP

Trojan se enorgullece de formar parte del proyecto de purificación de agua AIGUANEIX del Consorci d'Aigües Costa Brava Girona Trojan Technologies se complace en compartir que formamos parte del proyecto piloto de reutilización de agua AIGUANEIX de la Diputació de...

First Potable Reuse Demo Plant in Europe uses Trojan UV AOP

Trojan is proudly part of the Consorci d'Aigües Costa Brava Girona’s AIGUANEIX water purification project Trojan Technologies is excited to share that we’re part of Diputació de Girona and Consorci d'Aigües Costa Brava Girona’s AIGUANEIX water reuse pilot project at...

Trojan Technologies Opens First U.S. Distribution Facility in Grand Rapids, Michigan

On March 3, 2025, Trojan Technologies celebrated the grand opening of its first U.S. distribution center in Grand Rapids, Michigan. This strategic expansion underscores the company's dedication to enhancing customer experience and optimizing the delivery of its...